Today's Computers are Black Magic

Today’s computers are insanely fast and sophisticated. We don’t necessarily think of them that way, because they do such simple things like browse the web, read emails, and run dishwashers. Almost everything that uses electricity these days has a computer in it. We’re really seeing this with things like home automation, where even individual lightbulbs have small computers in them. They’re insanely cheap too, going to as little as $5 for something that can run a full operating system.

It’s easy to take this for granted, especially if you’re too young (as I am) to even remember the days of programming computers with punch cards. So I’m going to put some things into perspective.

Let’s take a trip back just 70 years, to the year 1947. Hitler was defeated just a short time ago, the USSR was budding into a global superpower, and computers were finally coming into their own. The prize American computer of the time was the ENIAC. It was paid for by the U.S. military (computers were originally machines of war), and came in costing $500,000. Of course, adjusted for inflation, this is somewhere between 6-7 million dollars.

It was a beast. The best of its kind. It was the machine with which the military assessed damage and calculated the impact of atomic bombs. It was the machine that opened the door for computers to be used, not just by the military, but by business. It was the machine that proved what computers were capable of.

Imagine the smartest person you can think of. Maybe it’s Einstein, maybe it’s Turing, or maybe it’s a name lost to time. Now imagine that all of their genius was focused on one thing: crunching numbers. Now imagine that they don’t need to eat or sleep, and just crunch numbers 24/7. Say they could perform 5 calculations every second (adding, subtracting, etc… huge numbers, like 31242363.21894), including writing them down. The ENIAC was like 100 of those people, all working in perfect unison.

In computer science, we have a term for this. It’s called floating point operations per second (FLOPS). In my example above, each genius was capable of 5 FLOPS. The ENIAC was capable of 500. So when I say that the ENIAC was powerful, and peerless, that’s where I’m coming from. The ENIAC dwarfed any one of these geniuses by a huge margin, and far surpassed the capabilities of any human that ever existed, or any machine that preceded it.

There’s a small computer you can buy called the Raspberry Pi 3. It costs just $35. That’s about 0.0005% of the adjusted price of the ENIAC. It’s capable of about 24 billion FLOPS. For those keeping score at home, that’s 48 million times faster than the ENIAC. For $35.

A 48,000,000x improvement. Over just 70 years. That kind of rapid improvement has never been matched in any other endeavor.

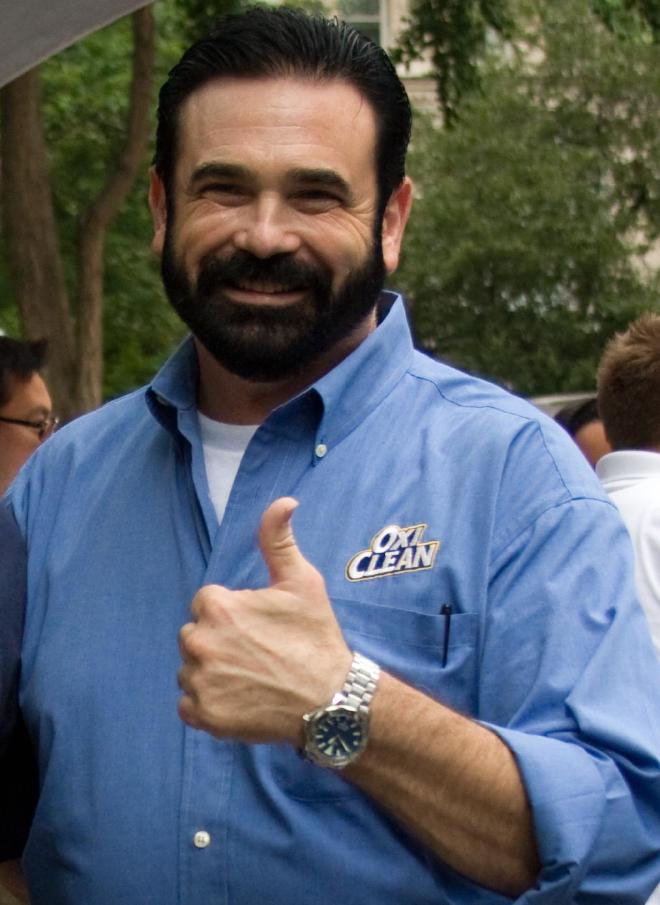

Now, in the words of the immortal BILLY MAYS: “BUT WAIT! THERE’S MORE!”

So lets take it a step further, with just a few more numbers (I know, I’m a nerd, but this is just too impressive for me to pass up). How much computing power could we buy for the price of the ENIAC? The Pi 3 is 48 million times faster, and costs a fraction of the price. Ignoring the fact that you can buy computing power by the hour for much cheaper than buying a Pi, let’s say for the sake of this example that we stockpile as many Pis as we can and see how much they can compute. At the price of $35/Pi, assuming the ENIAC cost $7M, we can buy 200,000 Raspberry Pis. That’s 96 trillion times the power of the ENIAC. That’s right, for the same price (adjusted for inflation), we have 96 trillion times the computing power.

70 years.

My phone is more powerful than a Pi 3. My laptop is. Your computer is too. This is what we use to check our email. To look at pictures of cats. Hell, to write a weird nerdy post about how powerful computers have gotten.

Computers have become so powerful, we take them for granted. They’re just a part of our daily lives, and we come into contact with computers (in cars, dishwashers, thermostats…) without even thinking about it. They’ve elevated to heights no one could’ve predicted, or even wrapped their head around less than a century ago.

That’s why we call this the information age. What would’ve been worth more than the entire Earth’s gross product a century ago now sits in all of our pockets. Information is cheap, it’s abundant, and it’s in everyone’s hands.